An audit walk...

November 2022 (1417 Words, 8 Minutes)

I’ve recently had the pleasure to perform an engagement focusing on compromising a well-known audit solution. After some basic analysis of the solution and specifically the various thick clients, we identified that the customer implemented the thick clients with LDAP SSO. This was found to be insecurely implemented and we eventually end up with some user impersonation attacks, reversing encrpytion and bypassing logical access to the Admin application.

Let’s start.. The application itself utilizes a configuration or connection file which should be copied with each instance of the software installed. Within these files, the encrypted credentials and configuration settings are stored. Remember this, as we’ll loop back soon.

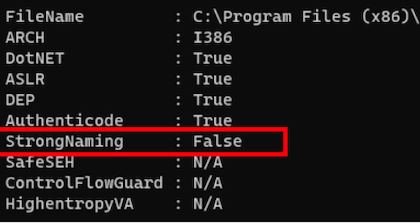

We set out to analyze two of the assemblies AdminPortal.exe and WorkingPapers.exe. Both are commonly distributed to users who utilize the solution. Our applications are developed in .net framework 4.7, which luckily meant we get to try our more focused .net debuggers instead of IDA, Ghidra reverse engineering tools focusing on a more low-level code. We note no code-obfuscation and no assembly validation are utilized by the applications. Looking into the binary protection, we could also readily identify the application hasn’t been compiled with Strong-named protections and we can leverage (although not perfect) the lack of protection.

Logical Access Bypass

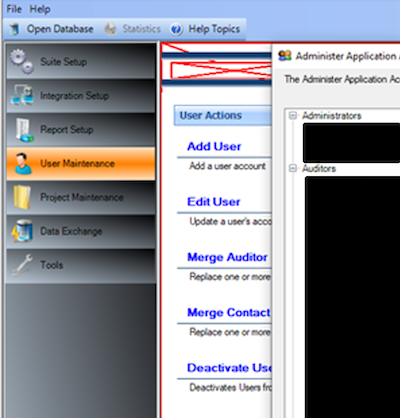

During the initial analyses, the AdminPortal.exe immediately became the primary focus as it is distributed with each installation of the solution. The Administrative portal allows administrators to add users, modify application settings, etc. In theory, if we could somehow obtain access to the Admin Portal, we could add users to the application, or even better the backend database.

We immediately open the application in our favorite .net debugger. We start browsing the code to obtain an understanding of the application’s flow from start to credential popup. There are various ways to go about this, for our purposes, searching keywords throughout the .net debugger source was enough to gain a good understanding.

By tracing some of the DLL imports, we identify a crucial library file Audit.Admin.UI.dll which contains most of the codebase of our AdminPortal.exe.

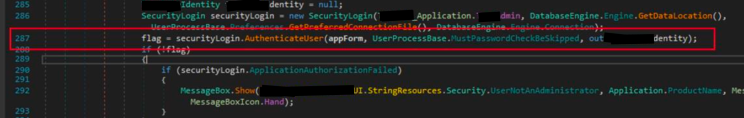

Within the Audit.Admin.UI namespace, we identify a class called UserProcessBase, which performs an authorization check. In layman’s term, if the current user’s Windows authentication is authorized to access the application, the result of this authorization check is stored within a boolean value true || false. Keep in mind the application has been set up with SSO.

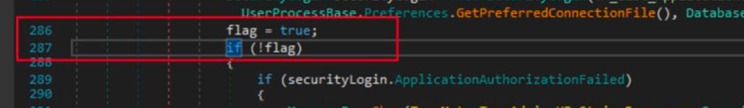

If the user is not authorized, the response from the AuthenticateUser method is false, and the security validation fails for the current user. This is a perfect location for us to bypass the application logic. If we can overwrite the result e.g. a permanent true the application will continue to load with all administrative functions available. The modification can easily be done with our .net debugger, and we modify line 287 for the code to read flag = true; instead.

We save our modification which results in a “patched” binary Audit.Admin.UI.dll. The patched file will bypass the SSO’s authorization check, automatically allowing all domain users administrative access.

We could simply copy the application files to a user-writeable directory and replace the referenced Audit.Admin.UI.dll file with our patched one. For all its good intentions, Strong-named assemblies might have helped here.

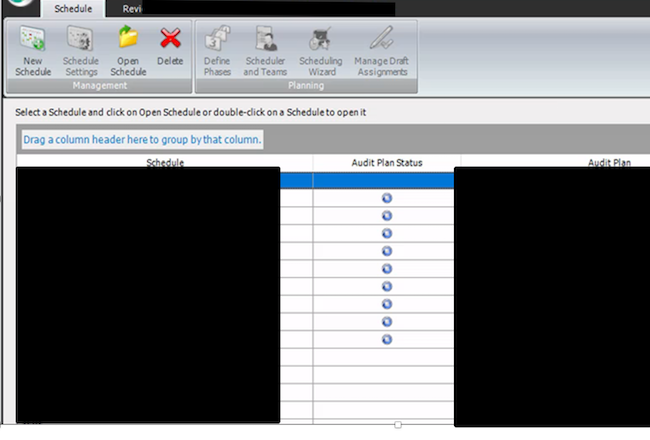

We opened the AdminPortal.exe application and, Magnifique!, our patch worked we can run the Admin application. We add ourselves to the application as local users and do some other fun stuff.

User Account Impersonation

Patching the application library files can also be used to impersonate other users, specifically useful in our WorkingPapers.exe type applications. Our impersonation can be done as the application utilizes SSO (Windows Authentication), which in the application’s logic extracts the username of the currently authenticated domain account and then utilizes the value to validate authentication and authorization for the application from the backend database, a flawed premise when manipulated.

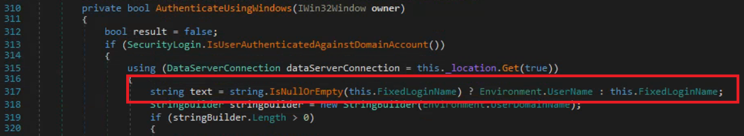

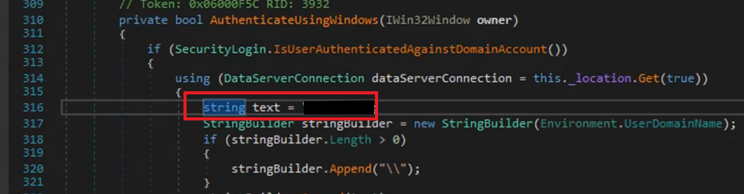

Unlike our AdminPortal.exe, the other applications utilize the username during several of the functions to extract data, the authorization checks, etc. within the application. Therefore, our normal domain joined account which hasn’t been added to the application’s database, will have no dice. We further dig into the application’s code and trace the function that extracts the username, this is done in the AuthenticateUsingWindows bool function, part of the Audit.Common.UI.Security.dll and the public class SecurityLogin.

We aim to inject a static username, which could be any application user’s domain account name. Patching the Audit.Common.UI.Security.dll binary would allow us to open various of the solution’s thick client applications as it is a common library file shared among the various applications. We, therefore, patched the code to always return the domain account name of an audit user administrator DOMAIN\EE1111.

We rerun our WorkingPapers.exe and the application loads successfully impersonating our DOMAIN\EE1111 user and we can continue to use the application on their behalf.

Hardcoding Encryption

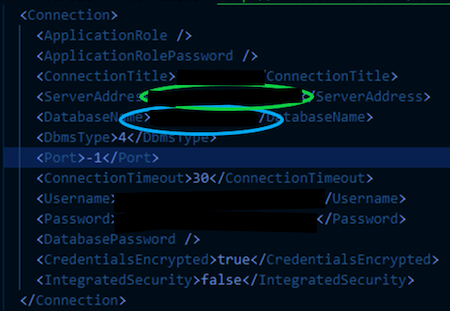

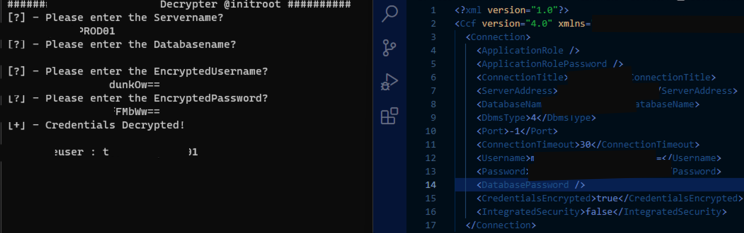

In both of the above instances, we’ve had the privilege of abusing the configuration or connection file which stores encrypted credentials to the backend SQL database. All of this would be better if we could have direct database access. Considering the credentials are encrypted, we start hunting the application flow for areas resolved around decryption. The below image outlines an example of the configuration or connection file.

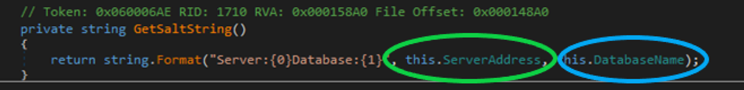

Based on code analysis in our .net debugger, the application utilizes the serverAddress and databaseName to generate a SALT value.

Therefore, we can easily obtain the values in cleartext viewable in the configuration or connection files. The below example is from the GetSaltString method under the namespace Audit.Common.Data of the Audit.Common.Data.dll file, which is invoked by a DecryptCredentials method.

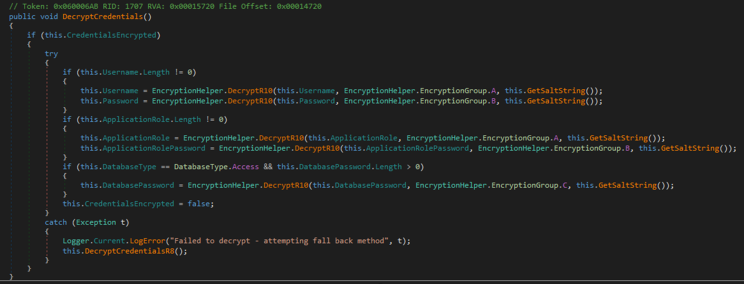

We identify that the helper library namespace Admin.Common.Utilities.Extract has several of the encryption values hard coded. We first look at the DecryptCredentials method. Within the method, the DecryptR10 function is responsible for decrypting the credentials, requiring the GetSaltString result. These result are hardcoded the in the configuration or connection files which include our encrypted username and password values.

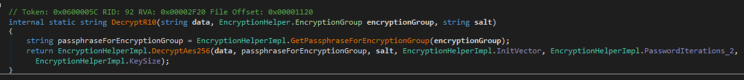

We further examine the DecryptR10 function. Ignoring the choice of encryption, we now already know a crucial part of reconstructing the overall process.

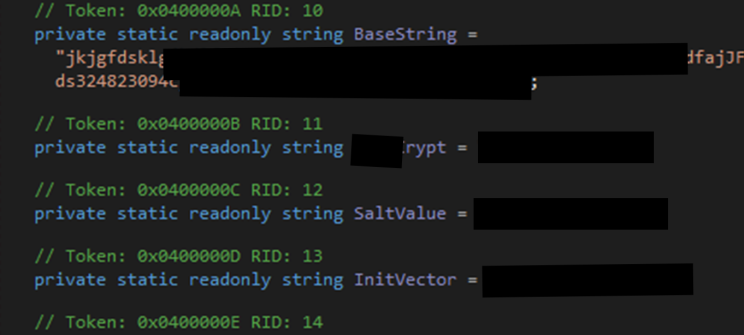

We further trace the application code for each of the values used in the encryption process until we find their origins. Hardcoded within the application source! A similar trend to our SALT values.

Jackpot, we now have all values required to reconstruct the decryption process. We mostly copy and paste from our .net debugger and create a decryption utility that receives the SALT and encrypted credentials from our configuration or connection file.

That’s a wrap, the above ignores simpler methods such as using .net SmokeTest, or dynamic analysis with our .net debugger to simply read the values from memory.

The Web SOO

In the end, we could find several other issues relating to the flawed SSO implementation, however, web applications utilising the SSO (web ntlm) became our next target. We can utilize our decryption process, to reconstruct encrypted values. Upon analyzing the web application’s server library files, we identified that the same encryption and decryption helper functions are utilized. (Same hardcoded keys etc.)

The SSO implementation of the web application utilizes the current authenticated domain username, with a unique SSO_Cookie which is sent on each request and used by the server for validation; this SSO_Cookie upon analysis, is constructed and encrypted based on the ConnectionTitle value in our configuration or connection files. This ultimately means the web application trusts any domain-joined user account as an authenticated user, as long as the encrypted SSO_Cookie value is sent and the web NTLM authentication username is found within the database.

All we have left to do here is connect to the database using our decrypted credentials, and replace an application used within the database with our domain username. We could also create a user directly, however, you must carefully manage all the constraints.

Final Words

Ultimately I had great fun. From the overall solution point of view, it’s important for a layered security approach in protecting binary files from malicious modification. The following can be considered:

- Do not store encryption values in cleartext within the application code.

- Code obfuscation. Ensure application codes are adequately protected from decompilation.

- Strong-named assemblies with signed files and a custom check within binary files to verify the hash of the loaded file.

- Threat model reliance on client-side controls, specifically with custom-made SSO implementations. Abstract critical/sensitive pieces of functionality to reduce over-reliance.